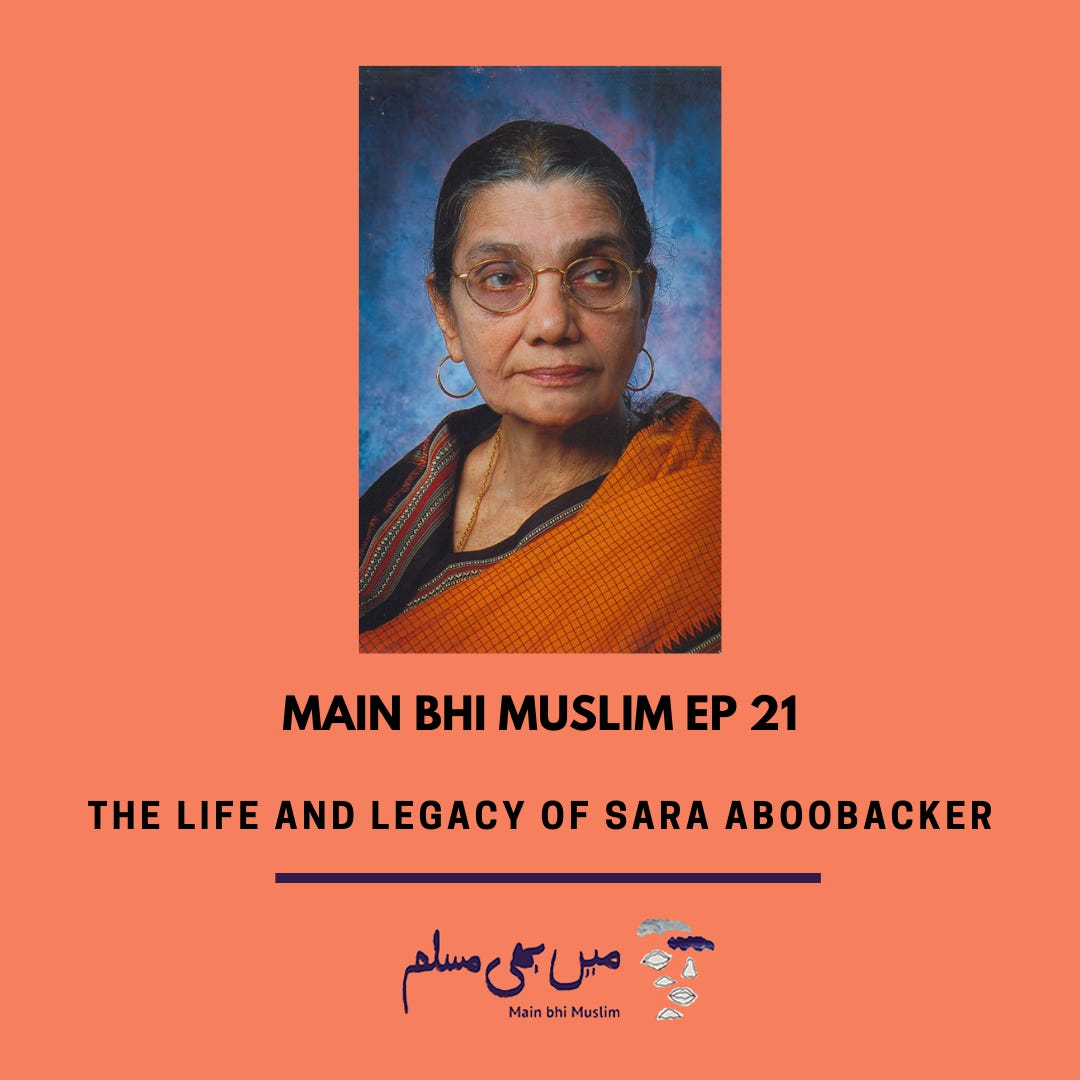

This conversation is between Dr Sabiha Bhoomigowda, retired Vice Chancellor of Karnataka State Women’s Akkamahadevi University, Vijayapura, and scholar Dr Sukanya Kanarally who has kindly interviewed Dr Sabiha on behalf of MBM. Dr Sabiha is a literary critic and was a friend of the late Kannada author, Sara Aboobacker.

This episode is dedicated to discussing Sara Aboobacker’s journey as a writer that was deeply influenced by her background as a Muslim woman from the Beary community - predominantly based in the South-Western coast of India. Sara wrote about the issues and prejudices concerning Muslim women within the community often at the hands of the clergy class.

Her breakthrough novel, Chandragiriya Teeradalli, translated into English as Breaking Ties or Nadira, established her as the leading Muslim woman writer in Kannada literature. A progressive writer, she used her voice and writing as mediums not just to express support for Muslim women’s rights, but also gender equality, women’s education, communal harmony and stand against caste or religious-based discrimination, violence and injustice. She was awarded the Karnataka Sahitya Akademi Award in 1984; followed by other recognitions for her contribution to Kannada literature.

Sara Aboobacker passed away in January 2023 at the age of 87, but has left behind a legacy of progressive writings and thinking that continues to influence writers and scholars beyond Kannada literature.

This interview was conducted in Kannada, and the English transcript can be found below.

About Dr Sabiha Bhoomigowda (published with permission by the scholar)

Dr. Sabiha Bhoomigowda, retired Vice Chancellor of Karnataka State Women’s Akkamahadevi University, Vijayapura, began her career as an Assistant Professor in Kannada at SVP College, Mangalore and continued to serve as a Professor and Head of the Department of Kannada. She served as the Director-in-charge at the Centre for Post-graduate Studies, Mangalore University, at Chikka Aluvara. She has successfully completed seven research projects alongside supervising many students in their doctoral research.

Dr. Sabiha Bhoomigowda is a writer too. She has published twenty books that span across genres like poetry, short story, essay, life story, literary criticism, column writing, and women’s studies. She has known Sara Aboobacker from close quarters as a friend and a critic. She has been one of the editors of Sara Aboobacker’s felicitation volume. She has also co-edited twenty seven research and literary works. Several of her poems, short stories and essays have been anthologised in the university textbooks.

Dr. Sabiha Bhoomigowda strongly believes that there should be no chasm between academics and social activism and that the society truly benefits only from such integrity. She has served as the President of Karavali Women Writers and Readers for two terms. She has also been serving Karnataka State Federation for Atrocity Against Women since its very inception.

Selected episode notes

Sara Aboobacker’s biography (Sahitya Akademi, 2011)

Sara Aboobacker, a Critical Insider Who Challenged Gender Hegemony and Oppression (The Wire, 2023)

The Brahmanisation of Textbooks in Karnataka (Round Table India, 2022)

Selected Writings by Sara Aboobacker (The Library of Congress)

Sara Aboobacker, Kannada writer, passes away (The Hindu, 2023)

Interview Transcript

Host: How has Sara Aboobacker contributed to women’s writing in Kannada and larger Indian literature?

Dr Sabiha Bhoomigowda: Sara Aboobacker (1936-2023) is identified as the first Muslim woman writer in Kannada. True there was another writer by name Mumtaz from Dakshina Kannada, the same region that Sara also hailed from. She had published stories seven to eight years earlier than Sara. But conventionally someone who builds a literary career over the years is identified as the pioneer. Hence Sara is the first matrilineal figure in the Muslim women’s writing in Kannada.

It is significant that Sara began her writing career the eighties of the last century. Kannada Rebel Literature (Bandaya Sahitya) was at its peak during those days. It was the time in which several fringe communities had begun to express themselves in writing. Lankesh Patrike, a weekly in Kannada with a byline ‘kannada jaana jaaneyara vaarapatrike’ ( a Kannada weekly for the discerning men and women) was a stage on which such writers found a voice. Sara was one of them. Lankesh Patrike was committed to providing a critical space for marginalised sections like Dalit, women, and minorities. She wrote a letter to the Patrike condemning the fatwa passed against a woman called Najma Bhangi from Bijapur for watching a movie. That incident marked the beginning of her writing career.

Sara represents the Dakshina Kannada district that Bolwar Mahammad Kunhi and Fakir Muhammad Katpadi who had begun to write even earlier hail from. The concerns and objectives of the trio were centred around the anti-woman practices in the Muslim community. While Boluvaru and Katpadi wrote from a male perspective, yet woman-sensitive, Sara wrote as a complete insider.

Thus Sara’s writing becomes significant on account of introducing the Muslim world that had been unfamiliar and hence the ‘other’ to Kannada reading public. Her literary career began with a short article and extended into other realms of literature like novel, short story, translation, radio-play, drama, travelogue, and autobiography.

Host: Sara Aboobacker's writings mostly focused on the challenges faced by Muslim women, due to religious orthodoxy and patriarchal attitudes within the Beary community. Can you explain to the listeners what were some of the main issues she wrote about in her writings?

Dr Sabiha Bhoomigowda: As you have rightly identified, Sara’s writing is a sharp critique of the religious fundamentalist practices of the priestly class of the Beary community that are an embodiment of male hegemony and oppression of women. The recurrent themes in her writing can be identified as follows:

Easy talaq

Polygamy

Child marriage

Unbridled reproduction

Domestic abuse

Misinterpretation of Shariat

Short cuts for reuniting the separated couple

Gender biased rules and rituals

Exploitation of the socially weak sections by the privileged class that rules Jamat

Misinterpretation of the women’s right to education, marriage, separation and other such issues that are inherent in the religion.

Host: What kind of opposition did Aboobacker face when she first published Chandragiriya Teeradalli? [The story has been translated and published in English under the title ‘Breaking Ties’ or ‘Nadira’]

Dr Sabiha Bhoomigowda: It was the year 1985. Sara’s novel Chandragiriya Teeradalli (ಚಂದ್ರಗಿರಿಯ ತೀರದಲ್ಲಿ), published a year before, had created a sensation in the Kannada literary world. Bandaya Sahitya activists had organised a seminar on ‘community studies’ in Puttur, located near Mangalore. Sara had been invited to speak on her recently published novel. A pandemonium broke loose in the audience at the very moment she rose to speak.

Several young men were bawling out. Some of them threw brooms at Sara. When the organisers stood in between the audience and Sara, some of the protesters picked up the chairs around and threw them at her. One could see that the protesters belonged to the Muslim community. ‘What kind of a Muslim woman is she who sits among men on the stage, without a burqa at that, and even dares to give a speech?’ - was the apparent cause of their ire. But the real reason was that she had exposed, in her very first novel, the vicious circle of easy talaq and the unholy short cut for reuniting the separated couple. An elderly Muslim gentleman’s earnest attempt to restrain the attackers saying that attacking a woman was totally un-Islamic was grossly ignored.

Sara had not walked up the stage in the past three decades. She had stayed away from the public platforms ever since her school days. It was only with great hesitation that she had now consented to appear on the stage. But she didn’t get a chance to utter even a single word. Seeing her back home safely became the utmost concern of the organisers. I was an eye witness to what unfolded on that day. And that was the first time I saw Sara in person too.

The next day it was hot news in the newspapers all over Karnataka. Several progressive organisations condemned the attack and held demonstrations supporting Sara. Recollecting the day, she had later remarked in one of her interviews, ‘if the fundamentalists had not attacked me, perhaps I would never have got this amount of publicity or awards.’ However, what is more important here is that the incident had failed to deter Sara from writing. She took it as a challenge and wrote again and again. She even appeared more often on the public stages thereafter! The strength and support her husband and family extended played a vital role in her life journey.

Host: Sara Aboobacker’s father was a lawyer and records claim that she used to listen to stories of women who’d visit her father for legal support. Can you share more about her father’s influence on her life as a writer?

Dr Sabiha Bhoomigowda: Sara’s father, P. Mohammad was a famous advocate in Kasaragod. He had received gold medal in Mohammaden Law from Madras University. He was a religious man and a local samaritan. His determination to get his daughter married only after she graduated from secondary school indicates his faith in women’s right to education. Sara’s mother Fathima, though confined to her home, listened and responded empathetically to the hardships of women around her. This streak of compassion in Sara’s parents seems to have had a decisive influence in the formation of her personality.

Sara’s father’s support to her writing was immense. As she said, someone from Mangalore approached her father and said, ‘Your daughter is writing against Islam. Blasphemy! Ask her not to carry on with it.’ Her father responded with, ‘Who should say what is right and what is wrong when it comes to religion? I have been reading everything she writes. I know there is nothing against Islam there.’ Sara could stand strong with such a background of support.

I remember another incident related to a weekly called Sanmarga (ಸನ್ಮಾರ್ಗ) that was being published from Mangalore. This journal was dead against Sara’s writing. It was the time when Sara’s husband had died and she was observing hidda, the period of mourning. Sanmarga carried an article against Sara and circulated a directive that Sara be excommunicated from Islam. Sara sought her father’s advice and filed a defamation case against Sanmarga and Muslim Writers’ Association. After a long drawn legal battle that lasted for four years, the verdict was out in Sara’s favour. Such incidents only strengthened Sara’s determination. Her husband too had been as supportive as her father.

Host: Aboobacker’s writings mostly focus on the working and clergy-class Muslims in the Beary community. What are some of the other writings where she wrote about characters from outside the community?

Dr Sabiha Bhoomigowda: What you say is true in relation to the nine novels that Sara penned. What she has written about people outside the community is almost negligible. As cited by Subraya Chokkadi, her talavodeda doniyalli (ತಳವೊಡೆದ ದೋಣಿಯಲ್ಲಿ) was published in Lankesh Patrike in the 1980s. Later it was published as a book in 1997. The novel centred around the corruption in the Department of Irrigation of the state. An honest Muslim engineer, unable to come to terms with such state of affairs for long years, opts for a transfer to Tungabhadra project just before his retirement. Sara has portrayed life and characters outside the Muslim community in this novel. The fieldwork she did during her five to six months’ stay in Raichur helped her build the narrative. This has been a part of her life story too.

Ilijaru (ಇಳಿಜಾರು) published in 2011 is another novel in which we come across non-Muslim characters, even if sparsely. The narrative focuses on the intense pain and misery of a woman in relation to her husband’s sexual promiscuity. With a certain amount of rawness in them, they don’t come across to the reader as great works of fiction.

Panjara (ಪಂಜರ) published in 2004, however was a novel that focused on the non-Muslim world. The narrative builds on the trials and tribulations of a single mother outside the wedlock. Perhaps it was imperative that such a character be situated outside the community. Yet there was sufficient scope for controversy too. The male characters in the narrative are either ‘too good’ or ‘too bad’ and thus suffer from excessive idealisation.

Host: Outside of her novels and stories, how did Sara Aboobacker influence girls and women to resist unfairness and patriarchal conditions?

Dr Sabiha Bhoomigowda: Sara has influenced women to resist patriarchal system’s unfair demands on them as much in real life, or even more, as in her writing. She has, at various times, remarked that her participation in the community activities was mainly for the purpose of listening to women’s woes and ordeals. Scores of women visited her with their problems. She would counsel and guide them accordingly, the details of which she often shared with us. All this was highly unpalatable to the religious bigots.

I remember another incident too. Once the head of an NGO that worked closely with the Muslim community invited Sara to their centre thinking it would help build a rapport with the community. Naturally there was a talk followed by discussion. Guess what? The head of that centre was evicted from there by the powers that be. No, this is not fiction, but a fact since Sara herself has documented what the head of the centre had told her. All this points to the fear and anxiety that the men suffered from on account of Sara’s charisma and influence.

One should not fail to take note of the irony here. Sara’s gamut of writing had focused on the exploitation that the illiterate, lower-middle class and hard working labourers, particularly women, faced in the society. But she wrote in Kannada. There was no way it could reach those women who were deprived of education and thus it failed to influence them. So who were her readers? Non-muslims and a meagre number of Muslims, mostly men at that, who had opened their doors to education and Kannada. Times may have now changed. What I intend to point out is that Sara has influenced more through her consistent social contact, be it seminars, talks, or discussions, than through her writing.

Yet another dimension is that Sara boldly withstood all the humiliation and embarrassment that the fundamentalists threw at her in her way. At times, she was even barred from speaking. She relentlessly waged legal battles against them and succeeded too. Her life journey itself has been the greatest inspiration indeed.

Host: Professor Muzaffar Assadi has written, "Aboobacker was a critical insider, and her canvas was not confined to the issues of talaq, domestic violence, gender bias and gender stereotyping. She constructed the multiple identities of Muslim women through the interrogation of the text and the theology to parallel the experience of similar women of subaltern classes in India." Can you share more thoughts on this?

Dr Sabiha Bhoomigowda: All writers that opened themselves up to modern education right from the first generation may be termed as critical insiders. One may cite the very first novelist in Kannada who wrote Indirabayi to the ones writing in the present times. C N Ramachandran, a Kannada critic identifies it as ‘insider-outsider motif’. Sara was undoubtedly a critical insider of her community. She was a strong critic of the community policies and practices that went against the interests of women. Modern education gave her the impetus to try and humanise her community through writing. Prof. Muzafar Assadi observes that a Muslim woman writer has to balance religious faith on the one hand and raise gender concerns within the parliamentary framework of citizen’s rights on the other. Sara’s life and writing embody such a fine balance.

Regarding the subaltern perspective, let me try to explain. Sara comes from the Beary language community in Dakshina Kannada. This small community consists of two and a half million people. She wrote during those times when basic education, let alone writing, was not accessible to women. A Beary Muslim woman writing was truly a revolution then! Radical Muslim men considered it a defiance flung at their face. Not just that! Writing in Kannada, a language of the kafirs? What more, Sara had raised her voice against the age old faith that women should unquestioningly follow the male hegemony and the religious laws. She questioned, she resisted, and she even campaigned against it. I wouldn’t so much as term it ‘subaltern’ myself. Were she to be asked such a question, she would have innocently said, ‘Oh, is that what they call it?’

She was a secondary school graduate. Born and brought up in a not so religious Kasargod, she married and came to a conservative Mangalore. A young and wide-eyed Sara discerned the gender stereotypes and domestic abuse prevalent in her community. She wrote in complete earnestness so that her community could leave the stagnant waters that it was neck-deep steeped in and open itself to the fresh breeze of change. As critics, we thus attribute several layers of identity to her. She is a woman, a Muslim woman, a Beary language Muslim woman who represented a very small minority community on the canvas of a large socio-cultural India.

Host: In some of her writings, Sara Aboobacker has shown the value of female friendships, such as Paatu and Amina in The Scorching Sun, Paru in Breaking Ties - was this a unique element in literature unexplored by other writers?

Dr Sabiha Bhoomigowda: Sisterhood is not a major theme in Sara’s writing. I think it is only partial and incidental. One reason may be her choice of characters, their lifestyles, surroundings, situations, illiteracy, lack of access to the outside world and so on. Another may be my own limited reading, I am not sure.

Banu Mushtaq wrote as Sara’s contemporary and continues to write in the present. Sisterhood is a clear theme in her writing. A reader cannot miss the deftly depicted sisterhood in her stories. Nevertheless, comparing Sara and Banu may not be fair. Banu is a lawyer by profession and her exposure to the outside world is decisively greater. Both come from sharply different backgrounds and their life journeys have been markedly different. Obviously the sections of society they represent are not much comparable.

Host: Last year, the Karnataka government removed many progressive Kannada writers’ works from Class 1- 10 textbooks’ curriculum, including Sara Aboobacker’s. How can one keep her literature alive within the younger generation? [This question refers to the previous government’s decision]

Dr Sabiha Bhoomigowda: It is true that the present BJP government has removed several literary pieces like story, poem, essay etc by the progressive minded writers from the school textbooks. Some writers have even opted out since they do not want to be a part of the reactionary curriculum. Who knows if this government will win the next elections too? Another government, another textbook committee, and another editor will certainly bring about a change of scene. But the point is this. In the hands of excessive centralisation in textbook policy, regionality will greatly suffer. Such a casualty is not restricted only to Sara’s writing. Several works of our literary stalwarts have also been pushed into oblivion.

Given the present scenario, I think the public libraries may be one window that will keep Sara’s writings alive. E-books is another option. There has been an attempt to re-read her writings after her death, under the pretext of paying tributes. Since most of her books were published by her own family publication, it becomes a family responsibility to make sure that they are available. Translating her works into English and making it available to the larger reading public is yet another option. As I have observed, except Chandragiriya Teeradalli’, the rest have hardly been translated into English. Translation is a way of preserving history for posterity.

Host: What would you consider Sara Aboobacker’s most important piece of writing, her legacy and why?

Dr Sabiha Bhoomigowda: I think Chandragiriya Teeradalli and Sahana are her two major works. The rest seem to be extensions of these two. However, several of her short stories stand well the test of literary quality.

I personally identify Sara’s legacy in her non-fiction. Among the women writers in Karnataka, Sara stands the tallest by the way she identified herself with the political, social and religious phenomena of her times. There may be some ideological limitations to her thinking. But she spoke out, wrote, and published in several fora including daily newspapers. As an informed citizen, she made sure that her thoughts were not only expressed in her literary works but reached the common people of her times too. Legacy is a matter of continuity. The next links of this legacy are nowhere in sight, as of now. True there are women writers who have been producing more robust works than her. But Sara was a ‘thought sphere’ by herself. She responded to religion, state, society, education policy and so on in a way that had a sense of great urgency to it. She believed in shaping world views and worked relentlessly towards it. Let alone muslim woman writer, I do not see any Kannada woman writer in general who can continue her legacy of passionate social commitment. Such consistent dedication, I think, is Sara Aboobacker’s legacy.

Interview in Kannada conducted and English trancript by Dr. Sukanya Kanarally who received her doctorate from Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. She began her teaching career as an Assistant Professor in English. A writer, researcher and a translator, Dr. Kanarally has published several translation works in both English and Kannada. She edited the web journal gelathi.com that was dedicated for women’s writing in which she translated women writers across cultures. (Biography republished with permission by the scholar)

Visual identity design by Sunakshi Nigam || Music by Jupneet Singh